Context switching on an AVR

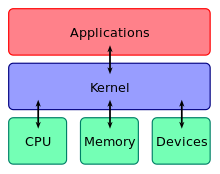

Modern operating systems are run on are complicated beasts. They consist of millions of lines of code, providing a wide range of functionality. At the core of these tasks is the ‘kernel’. This core section of the operating system has a single goal: providing a machine-independent abstraction of the hardware. The rest of the operating system and other applications can then be built on top of the kernel to use this interface, meaning that applications should run correctly on every machine type supported by the operating system kernel.

When using a computer, the functionality of the kernel is hidden away as much as possible - it’s merely there to provide services to applications. However, in order to really understand what the kernel does (or could be doing), it can be useful to implement a kernel for yourself.

Kernels are big and complicated so it immediately raises a question: what section of a kernel should we create? The diagram above splits out the hardware into three sections, CPU, memory and devices (eg. keyboard, mouse, display or speakers). Let’s focus on the first one - the processor. From a high level overview processors are simple. You feed them instructions, and those get executed. The tricky bits are in the details. How do you make the CPU load instructions when it isn’t on yet? Now it’s on, do you always run your CPU at full speed, or do you occasionally turn sections off to preserve battery power? What do you do if this specific CPU does not support an instruction used in the program? Lastly, kernels can execute more processses simultaneoulsy than the machine as processors. How do you make (it appear to) do so?

Context switching

The answer to the last question is deceptively simple. Assume we have some set of programs and a single processor that can execute one program. We start it off by telling it to execute the first program in the set. After a few milliseconds, we interrupt the processor and load the second program. Again, a few milliseconds later, we interrupt the processor and load the third program. This would work fine, assuming that programs only run for a few milliseconds - but in reality this is almost never the case. Therefore, after we’ve run every program in the set for a few milliseconds, we can start back at the beginning, giving each some more time before, again, being interrupted. We are essentially dividing up the full program execution of every program into little sections and interleaving those on a single processor, giving the appearance of all of them running simultaneously. However, the user application may have no idea that this is happening and therefore, we need to take care to preserve the state of the program. After each execution section, we store the state of the program to memory. This way, when the program gets its next bit of execution time, we can load the old state and start again where we left off. This makes the process transparent for the running program. As far as it knows, it simply never stopped executing as all values in the program are exactly the same, even though the processor has been executing a different program in the meantime.

This process is known as context switching, in which ‘context’ refers to the state of the program. This state is described by the internal state of the processor, meaning the registers. These contain often-used variables and information about the current execution, eg. what is the next instruction I should be executing. The memory (RAM) used by the process is usually not included as the ‘context’ of the process, but that is because every process already operates on its own bit of memory - which does not cause clashes when swapping out the executing program during a context switch.

Why on AVR?

To be continued with as much operating system as I can fit on an AVR - stay tuned.

Subscribe via RSS